Finding the Chorasmian glosses in Arabic manuscripts is not easy work. One has to closely examine numerous copies of the same work in order to find out whether some Chorasmian marginalia or short notes are present on a few folios, or not at all. While Yusuf Aǧa 5010, the main source of lexical material, has rather clearly-written glosses throughout, other copies of the Muqaddimat al-Adab have only a few, marginal Chorasmian words. Given just how many copies of that text exist, one doesn’t envy the scholars of previous generations who took it upon themselves to sift through thousands of folios in order to see if a given copy had any Chorasmian or not.

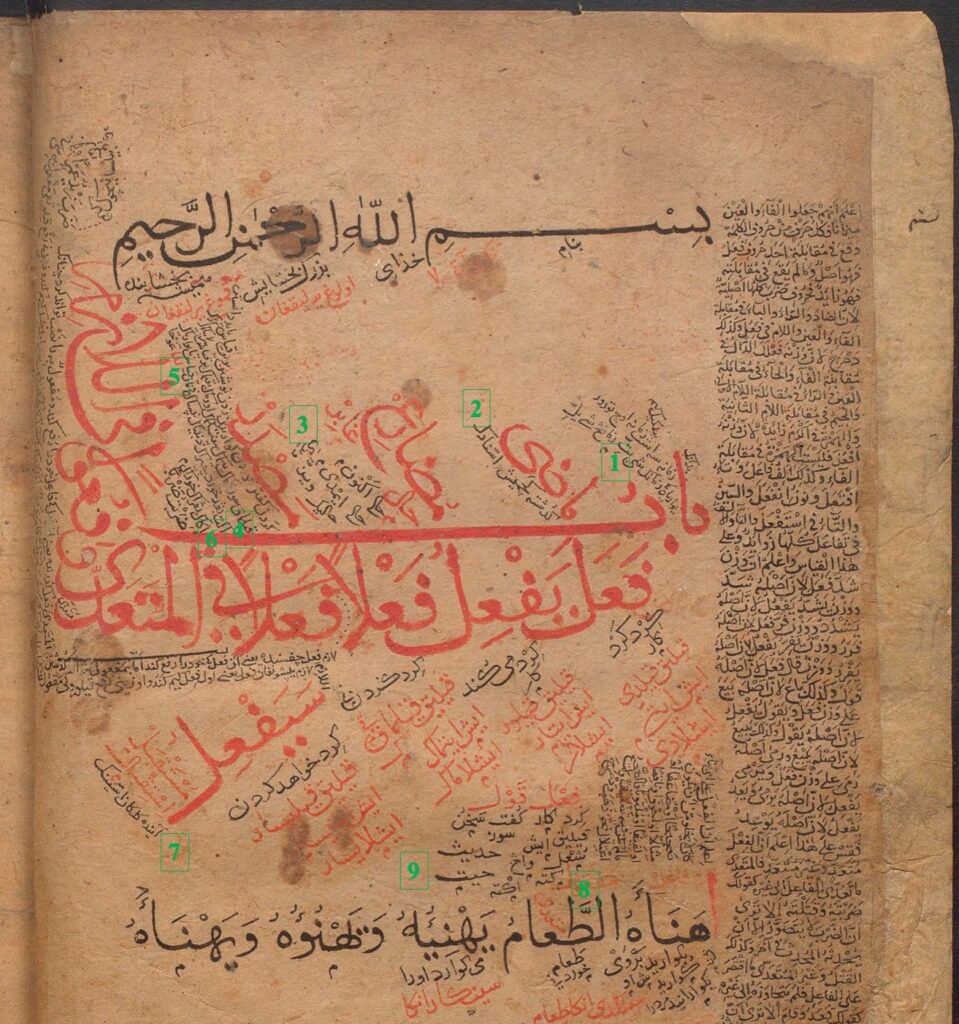

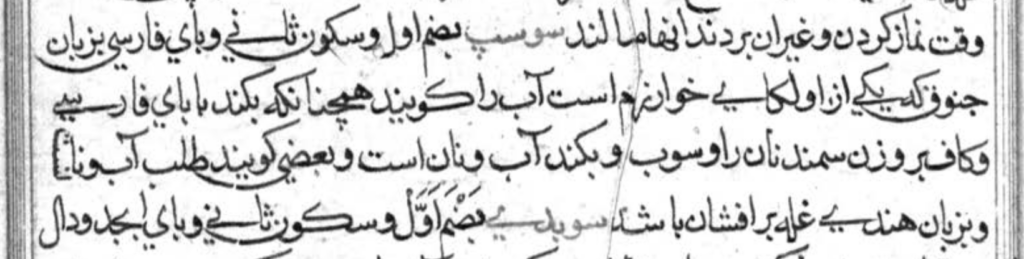

With British Library Add. MS 7429, a partial copy of the Muqaddima, David N. MacKenzie got rather lucky. There are Chorasmian glosses on the very first page, and only on that page, though tucked under and beside the more copious Persian glosses. One does wonder how far MacKenzie searched through the ms. before deciding there was no more Chorasmian to be found. Perhaps in a nod to that medieval scribe who wrote the Chorasmian, MacKenzie helpfully tucked his own announcement of the discovery of the glosses in this ms. and his edition thereof into a page in the middle of one of his reviews of Benzing’s Sprachmaterial (MacKenzie 1971: 524-525 “The Khwarezmian Glossary IV”). It was thus a while till I myself noticed this additional manuscript. A colophon for the section on particles (ḥurūf) dates Add. MS 7429 to Dhu ’l-Qa‘da 760 AH, or Oct. of 1359 CE—a date contemporary with the production of several other Chorasmian manuscripts.

Given that the glosses are so few, and the manuscript has been shared publicly by the BL, it will furnish a nice illustration of how Chorasmian glosses to the Muqaddima actually look. This particular ms. is glossed throughout in Persian and also has a few pages with glosses in what was then called “Eastern Turkish”, that is, Khwarezmian Turkic or early Chagatay.