Approximately concurrent with Henning’s late work on the Chorasmian lexicon in the 1960s, another effort was underway back in Germany. The German Turkologist (and Nazi cryptanalyst) Johannes Benzing (1913-2001) had begun editing the Chorasmian material preserved in the Muqaddimat al-Adab, primarily based on the manuscript Yusuf Aǧa 5010 held in Konya and published in facsimile by Togan in 1951. Benzing was not a scholar of Iranian languages, but was primarily interested in Chorasmian as a possible substrate language to the Turkic variety that became current in the region from the 13th century on (known as Khwarezmian Turkic or pre-Chagatay). His collection of this material published in 1968 (Das Chwaresmische Sprachmaterial einer Handschrift der “Muqaddimat al-Adab” von Zamaxšari) therefore ended up beset by problems.

The work is first of all something of an eclectic edition. Benzing combines his idiosyncratic transliteration of the Chorasmian glosses in the Konya manuscript with the Arabic and Persian equivalents and Latin translations as presented in the 1843 edition of the Muqaddima by Johannes G. Wetzstein (1815-1905). Benzing leans in the direction of a text edition, listing each word or form as it appears in order in the manuscript, rather than gathering them into an alphabetized grouping. As a guide to the Chorasmian lexicon, this means that the edition is rather hard to use. Moreover, as a guide to a single manuscript, its eclectic arrangement with ms pages mixed with the Wetzstein entry numbers means that it is confusing to peruse.

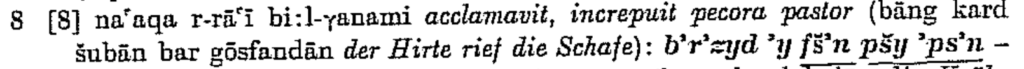

But the main problem was that Benzing made little effort to interpret the spellings of Chorasmian words, many of which were partially or totally unpointed. He used a complicated transliteration scheme to try to indicate what letters should have been pointed a certain way and which remained unclear. Lacking knowledge of Iranian languages and philology, he wasn’t able to resolve these problems through comparison and etymology, and ended up mis-presenting numerous words, many of which would have been decipherable, behind their unpointed Arabic skeletons, to someone with knowledge of Old or Middle Iranian. This is precisely what MacKenzie pointed out in a series of five (rather brutal) review articles on the book that he published from 1970 to 1972. His appraisal of the work can more or less be summed up by his statement that “Benzing can be faulted for many misreadings and, worse, wrong generalizations from them” (1970:541). These reviews are so extensive that reference to Chorasmian words preserved in the Muqaddima is simply not possible without them.

Other reviewers were equally critical, and it’s worth giving a taste of just how—for example Martin Schwartz wrote that “[Benzing]’s misunderstanding of the elementals of Khwar. orthorgraphy and phonology has grave repercussions,” and “as complicated and impractical as [Benzing’s transliteration] scheme is, it is assiduously betrayed by its inventor,” and indeed that his “interpretation of many entries suffer not only from his disregard of other entries, but from hasty or otherwise deficient analysis” (1970). On the bright side, the problems with this publication gave MacKenzie the opportunity to refine his own system of transliteration, and other scholars like Schwartz and Emmerick the chance to improve many Chorasmian etymologies.

The utility of Benzing’s book would have at least been improved if it had an index. He had planned to publish one separately, and had completed it in 1972, but shelved it because of MacKenzie’s critical reviews. His Chwaresmischer Wortindex, integrating some of MacKenzie’s feedback, was eventually published in 1983 at the instigation of Benzing’s Mainz colleague Helmut Humbach and edited by the latter’s student Zahra Taraf. The index is just that: 713 pages of pure, unadulterated word-forms. No explanatory text, just masses upon masses of typewritten, transliterated Chorasmian.

Unfortunately, the index didn’t really make the study of the Chorasmian all that much easier. Its organization is wanting: for example, the different forms belonging to one and the same word are listed alphabetically rather than grouped under one unifying heading. This means that present and imperfect forms of the same verb are sometimes hundreds of pages apart: e.g. for ‘to do’, ’k- (pres.) is on p. 42 while mk- (impf.) is on p. 406! Or, for example, the different spellings of δβr ‘door’ (including δβr, δβyr, dfr, dfyr) each get their own entry. These shortcomings, besides the difficulties with word analysis and etymology, make this index likewise difficult to use. As several reviewers pointed out, it was probably meant to be a working reference for Benzing rather than a publication. Skjærvø noted, dryly, that it was probably less legible than the original manuscript of the Muqaddima itself!

In the end, though, both Benzing’s Sprachmaterial and Chwaresmischer Wortindex hardly moved forward the study of the Chorasmian lexicon or that of the Muqaddima‘s multilingual glossing tradition. They did not build on Henning’s (largely unpublished) advances in Chorasmian philology, MacKenzie did not build on them in his own efforts towards a complete Chorasmian dictionary, and they’ve only seen citation (with copious correction and reference to further literature) in so far as they have been the closest thing to such a dictionary available in print. No longer very useful, they are a (weighty) dead branch in the modern history of Chorasmian philology.