The next major stage in the history of attempts to create a Chorasmian dictionary, and the second to be interrupted by death, is that of David N. MacKenzie (1926-2001). Initially a specialist in Pashto and Kurdish, MacKenzie moved into Old and Middle Iranian as a student of Henning at SOAS in the 1950s. As a faculty member of SOAS, by the mid-1960s, he had evidently become interested in Chorasmian (despite his own admission (1971:1) that he “never studied any appreciable amount of Khwarezmian” with Henning) and had begun studying the available material in earnest. Already in 1968 he had prepared a preliminary edition of the Qunyat al-Munya and its Chorasmian phrases, but this project was paused for several decades until he was able to obtain access to better manuscripts of the text from Soviet archives.

MacKenzie’s work towards a Chorasmian dictionary also seems to have begun in the late 1960s, even before he received the fragment of Henning’s dictionary which he edited and published in 1971. Indeed, it was his intimate familiarity with Chorasmian and its structure that enabled him to publish his extensive, critical reviews of Benzing’s work between 1970 and 1972. Although MacKenzie seems to have produced several kinds of preparatory material for a dictionary over the decades, he—like Henning—never published any of it during his lifetime, despite devoting much time to the project after his retirement in 1994. A glossary to his edition of the Qunya (1990) is thus his only published lexical material.

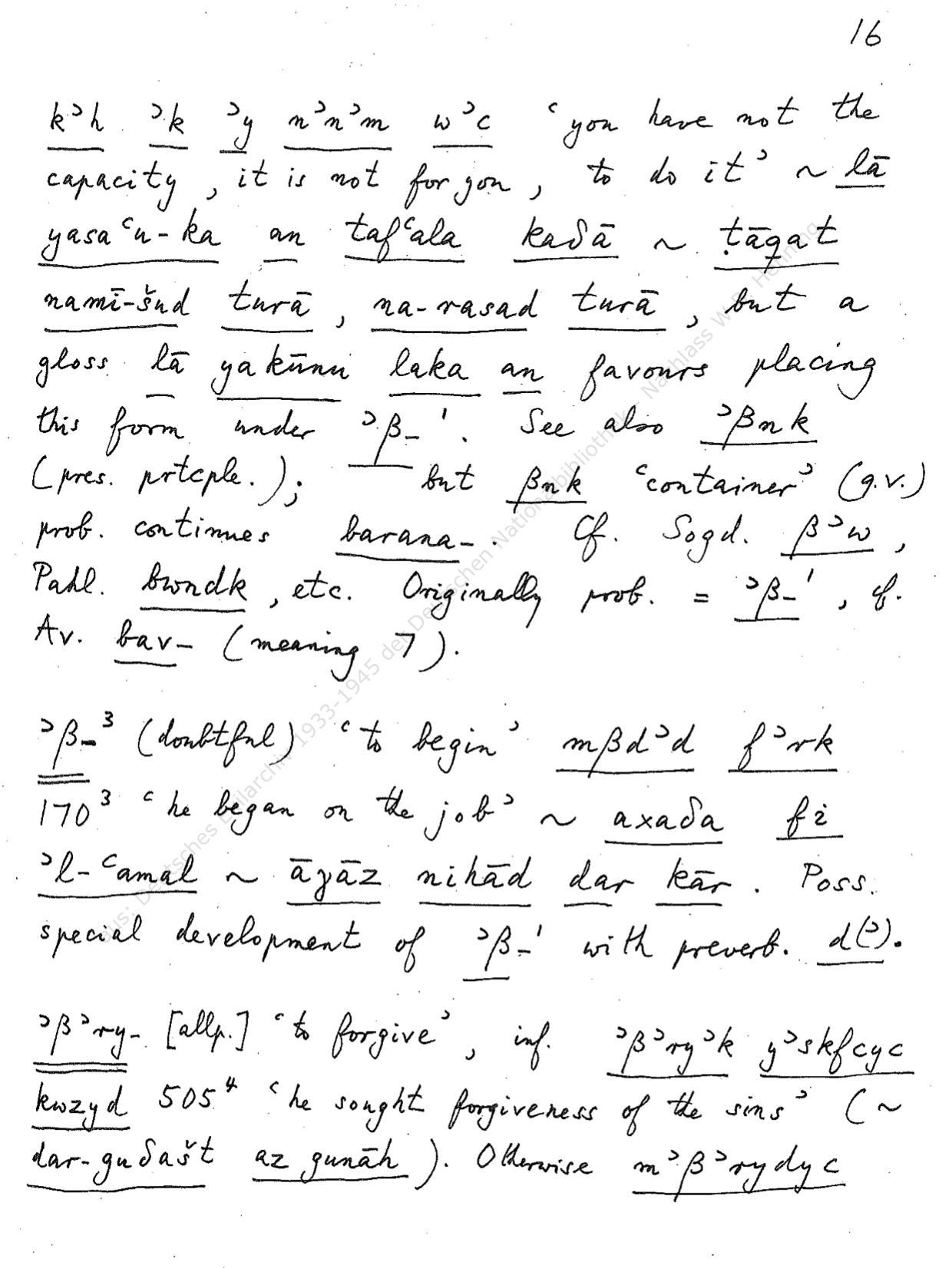

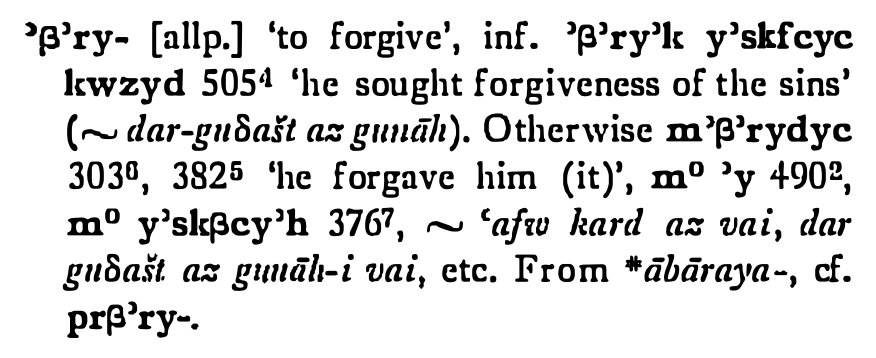

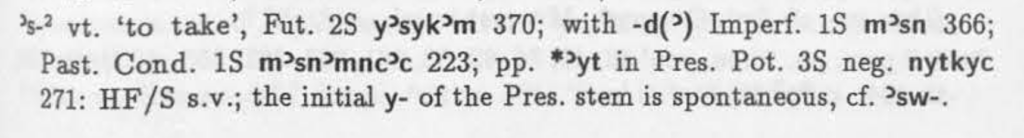

Once MacKenzie passed away and his Nachlass was made available to scholars interested in finishing some of his unfinished projects, some insight could be obtained into the—fairly significant—progress he had actually made on Chorasmian. As Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst first reported in English and German papers on Chorasmian lexicology (both 2005), MacKenzie had, sometime in 2001, printed out a close-to-final draft of his finished entries. According to my count, these total 1888 completed entries covering the letters from alif to most of ghayn (breaking down as follows: ʾalif 950 ʿayn 47 B/b 320 β 72 C/c 113 č 81 D/d 59, δ 90, F/f 65 G 1 Γ/γ 90). MacKenzie also had other kinds of materials in various states, including basic lists of all attested words, concordances to the texts in which they occur, handwritten/typed drafts of entries up to the letter n, and his own card catalog of the complete lexicon. It is clear as well that all his work on a dictionary was based on his own editions of all the existing Chorasmian material in Arabic script—besides the Qunya (1990), he also published corrected decipherments of the Yatīmat al-dahr family of manuscripts (1996).

It seems that MacKenzie envisaged his dictionary to have two main parts: the complete glossary with definitions and attestations, and a part with etymological discussion. The latter part, which he separated out from the former, probably in order to finish it more quickly, does not seem to be preserved (or perhaps was never really drafted). It is also unknown how much longer MacKenzie thought he needed to draft the remaining entries; it probably would have required a few more years. However, it is obvious from the existing near-final draft that he had essentially all of the Chorasmian material gathered and organized, and only needed to write it up into the format he chose for the lemmas. MacKenzie therefore got much further than did Henning, and his material was even more thorough—only to also unfortunately be bested by time.

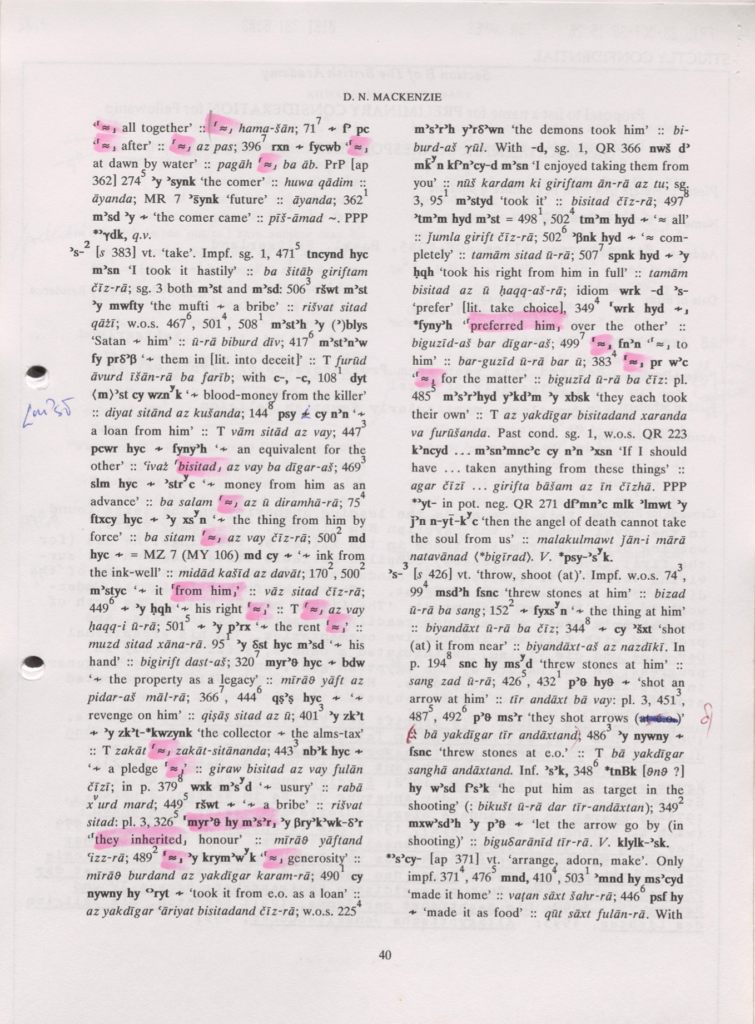

MacKenzie’s dictionary format largely follows that created by Henning decades previous, although with a slightly more thorough transliteration system, more extensive attestations of course, and a rather complex system of abbreviations which were probably designed to shorten the overall length of the work in print.

From the sample page above, one can see just how much more extensive the full dictionary is than previous published materials such as Henning’s Fragment or the glossary to Mackenzie’s Qunya. These are the materials—in the first place, the printed draft of the completed entries—which form the basis for the Chorasmian dictionary project. The existing materials as well as the project’s methods will be surveyed in the next blogpost in this series.