While the early years of the 20th century saw a massive boom in the number of Middle Iranian sources available to the world, the Chorasmian language remained almost unknown to modern scholars. That an Iranian language particular to the region had existed, of course, was no surprise: the polymath al-Biruni cited a few Chorasmian terms in some of his works, and al-Biruni’s works had been the subject of major European scholarly publications since the 1870s. But no Chorasmian sources were discovered at Silk Road sites such as Turfan, for example, which yielded such riches in Sogdian, Parthian, Middle Persian, and Khotanese. So, no actual sources in Chorasmian were known to that first modern generation of specialists in Middle Iranian.

The fact that original Chorasmian texts are now available to scholars, and have been studied since the mid-20th century, is due entirely to the efforts of one person: the Bashkir revolutionary and Turkologist Ahmed Zeki Validi Togan (1890-1970).

Originally trained in Islamic sciences before becoming involved in the Bashkir independence movement, Togan had a sixth sense for rare and unique manuscripts. For example, in 1923 while in Mashhad, Iran, he discovered the sole manuscript of Ahmad b. Faḍlān‘s famed 10th-century travelogue known simply as the Risāla. Then, after arriving in Turkey in the mid-1920s, Togan discovered a number of manuscripts with Arabic, containing Chorasmian writing in the Arabic script, in various archives around the country.

Togan first discovered multiple copies of the Yatīmat al-dahr fī fatāwa ahl al-‘aṣr in Istanbul libraries that had Chorasmian glosses (i.e. translations of Arabic sentences) and a copy of al-Zamakhshari’s Muqaddimat al-adab in Konya and Istanbul with a few Chorasmian notes to the Arabic and Persian definitions. Then in the early 1930s Togan discovered multiple manuscripts of the Qunyat al-munya fī tatmīm al-ġunya with hundreds of clear Chorasmian glosses. Continuously and painstakingly searching dozens of copies of the same text for unique marginalia or glosses, even after being imprisoned for his political activism, Togan found, in 1948, another copy of the Muqaddima, this time almost completely glossed in Chorasmian and thereby improving exponentially the lexicography of the language. [For brief explanations of all these texts and what they contain of Chorasmian, see the Manuscripts page]

Before Togan, scholars had no real clue about the nature of the languages of Chorasmia from the early Islamic era on, and it was thought that perhaps the language alluded to by al-Biruni had mostly died out by his time (~1000 CE). But with Togan’s discoveries, it became clear that Chorasmian had continued to be spoken and written until at least the 1300s CE, and perhaps passively understood even longer. The manuscripts that he discovered in Turkey provided the basis for nearly all subsequent work on the language for most of the 20th century, supplemented in parts by additional copies of the same texts found in other archives.

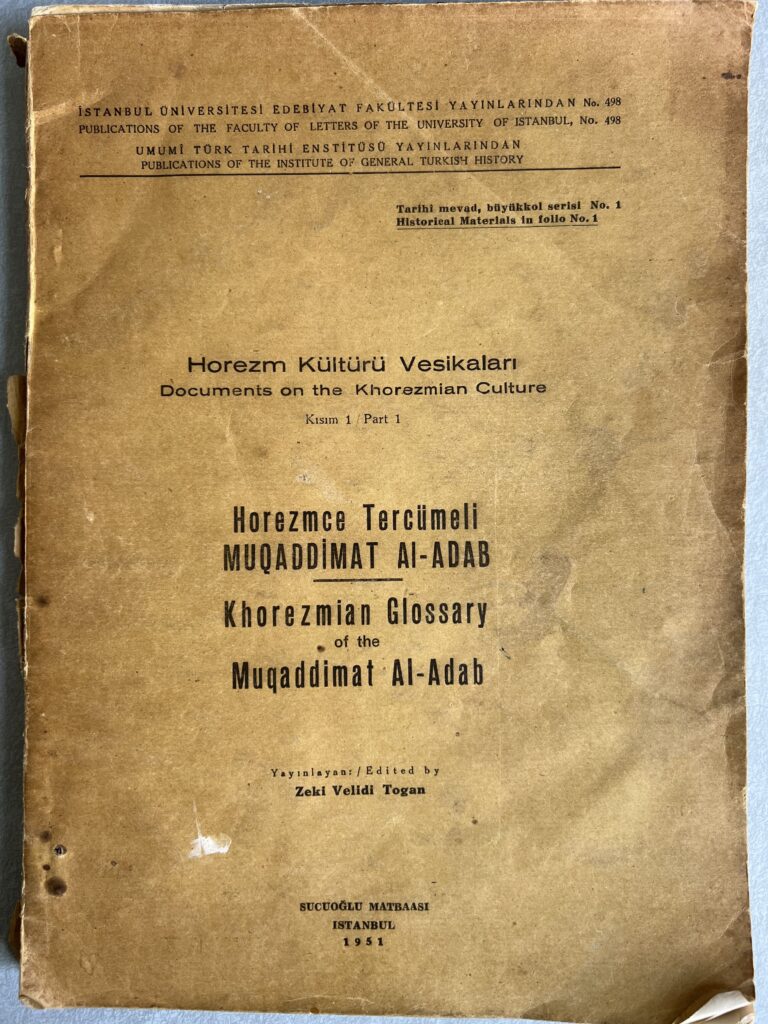

Though Togan did not do much philological work on the language itself, he published the first examples he discovered (Togan 1927), as well as, eventually, a full fascimile of the most extensive manuscript of the Muqaddimat al-adab (Togan 1951). And it was with Togan, during a 1936 sojourn in Bonn at the invitation of the Arabist Paul Kahle (1875-1964), that Walter B. Henning (1908-1967), who was to go on to do foundational work on Chorasmian, first studied the language (see Henning 1936, Togan 1936). However, Chorasmian remains the least studied of the Middle Iranian languages and few scholars have been devoted to it, or even dabbled in it, since the passing of David N. MacKenzie (1926-2001), who made serious advances in Chorasmian philology between the 1970s and 1990s, including achieving a long-awaited edition of the Qunya‘s Chorasmian parts (MacKenzie 1990). Part of this scholarly neglect is due to the inaccessibility of the primary sources, not to mention the inaccessibility of the existing modern scholarly studies, and the difficulty of the language itself. Another part is due to there having been few to no active scholars teaching the language anywhere in the world. While this latter issue can’t be solved here on this site alone, unfortunately, sharing the history of the scholarship and resources for its study online hopefully will help with the former. No doubt Togan, who discovered and shared such fundamental resources in a variety of literary and linguistic areas, would support such a cause.