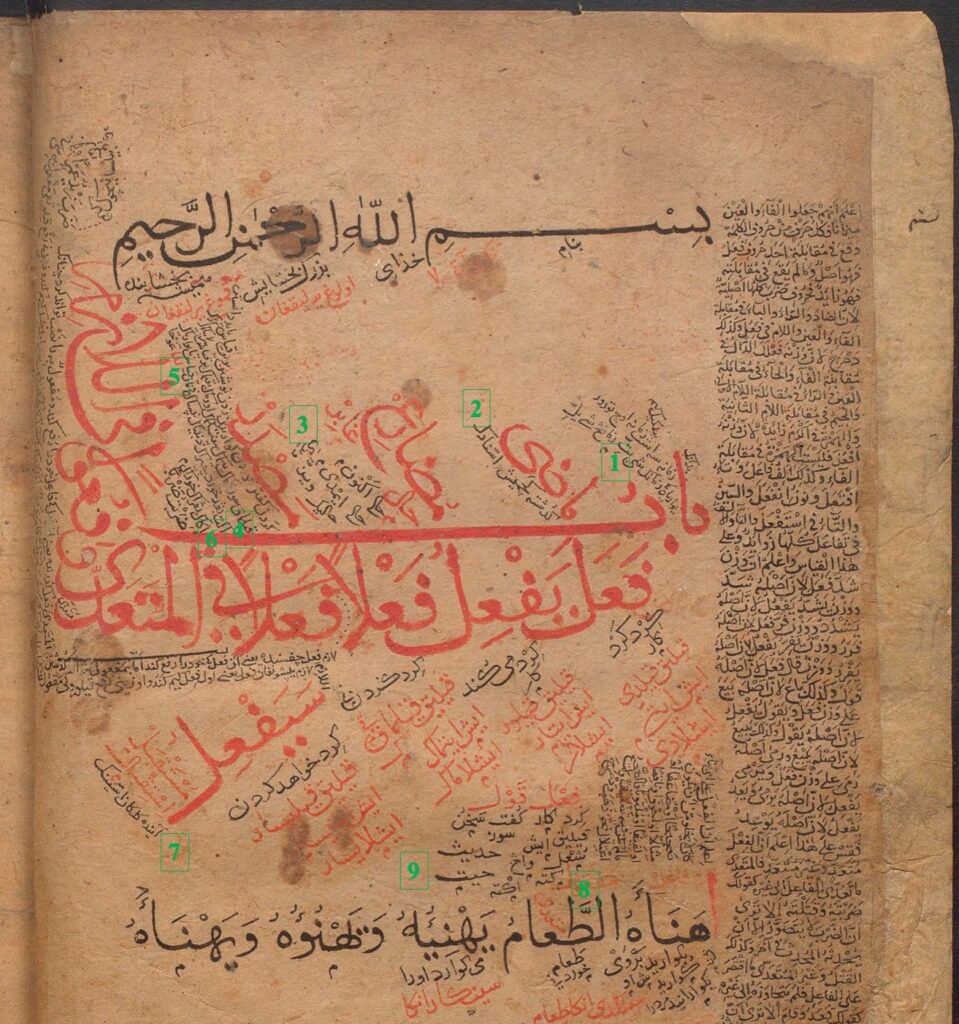

Producing a dictionary of the Chorasmian language has been a goal within Iranian philology for about seven decades. Two major figures in the field, Henning and MacKenzie, dedicated a significant part of their careers to that goal—and both were unable to finish their work or make much available to the public before their deaths. Fortunately, the materials left behind by both scholars provide a solid foundation to attain this goal, indeed, perhaps even all the necessary building blocks. In this post, I aim in the first part to overview these existing materials and in the second to discuss the approach to compiling and organizing them to produce an online and accessible dictionary of Chorasmian.

Part 1: Existing unpublished sources

To compile a (non-etymological) dictionary, the following materials are the primary foundation:

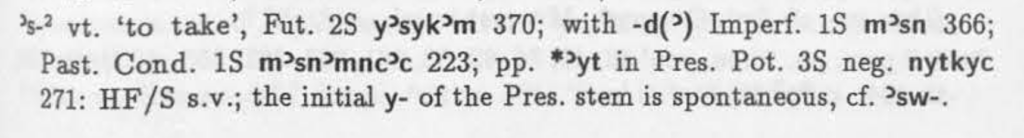

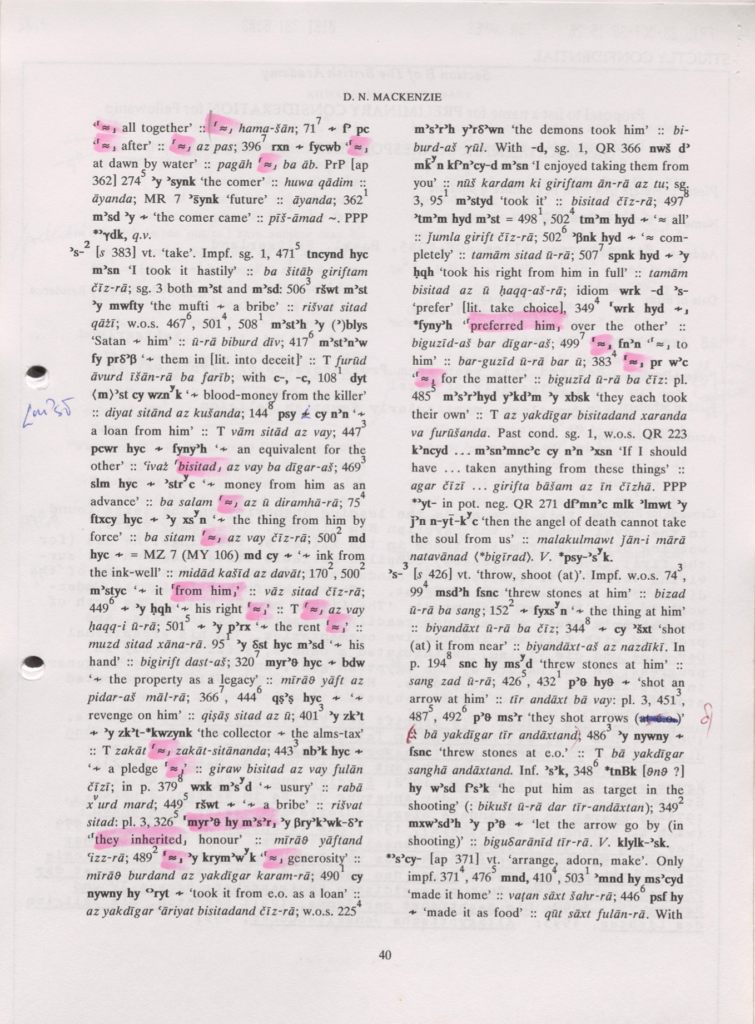

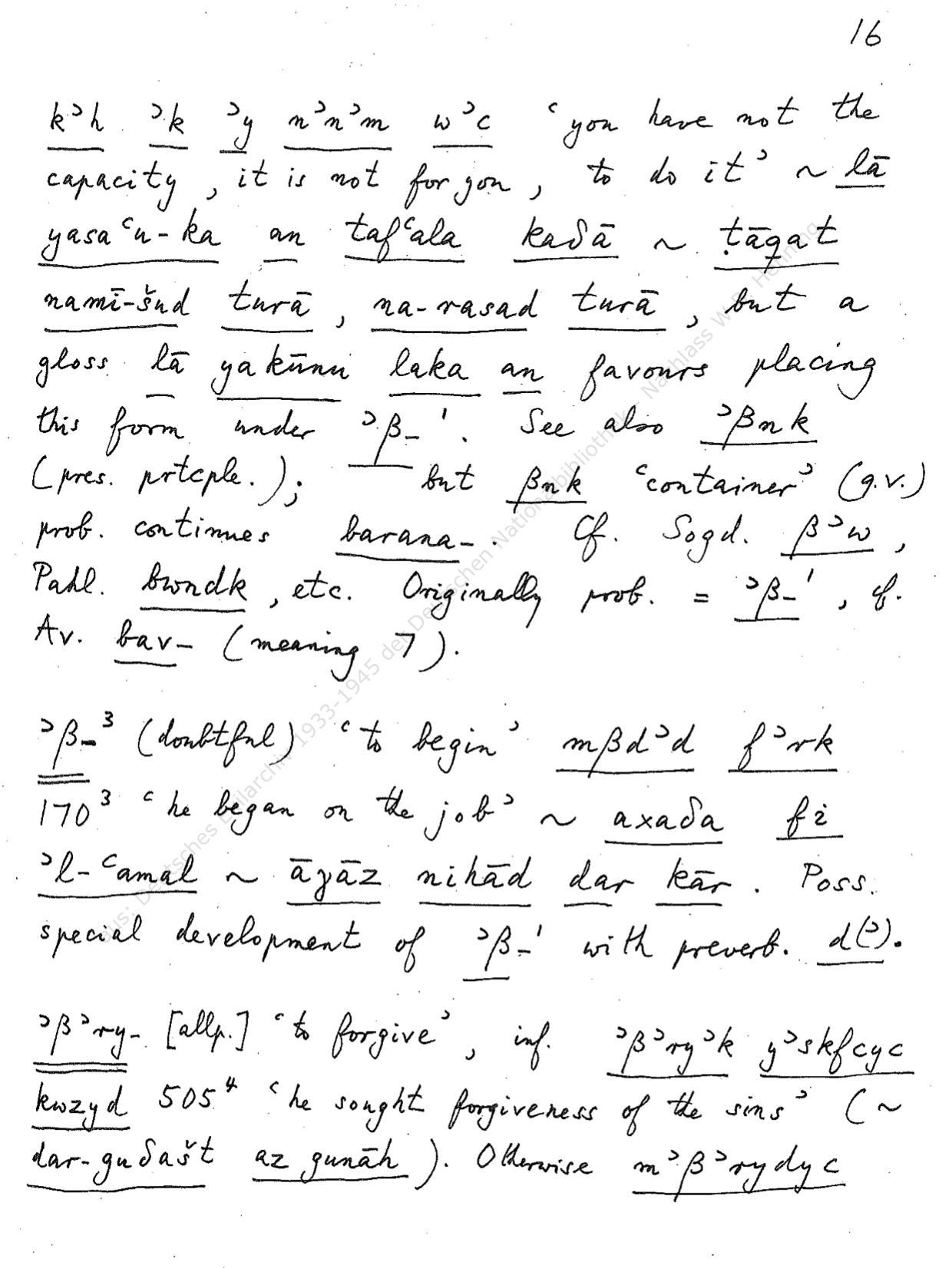

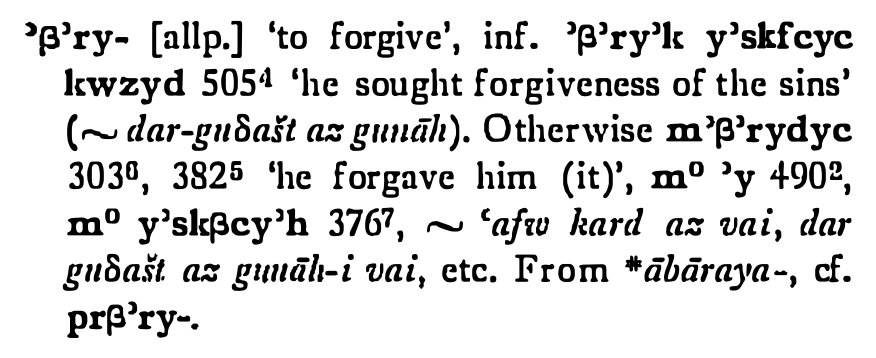

- A draft printout of completed entries ʾ- through γw-, almost 1900 entries together with a slightly older version of the corresponding digital file (MacKenzie)

- An older and less complete draft entries of ʾ- through n- on paper (MacKenzie)

- Printed and digital versions of the concordance of the entire lexicon, organized alphabetically (MacKenzie)

- Computer files containing the Chorasmian words and phrases in each source text (MacKenzie)

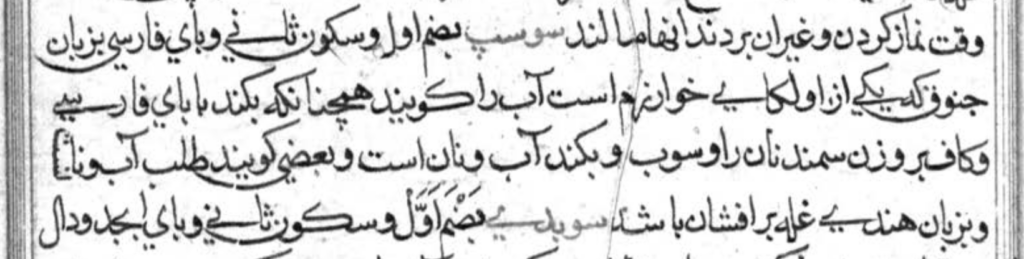

- Handwritten index cards of the entire lexicon (MacKenzie, Henning)

The most recent work seems to be the print-out of ʾ– through γw-, probably dating to mid-2001 a few months before MacKenzie’s death. His computer file for ʾ– through γwxy– is very slightly different than the print-out, mostly in the format of lemmas, and seems to be a slightly older version. This draft of almost the whole of alif through ghayn, about 1900 completed entries, is essentially complete and can be used verbatim as the basis for the dictionary (but will be reformatted, see below). These probably constitute 30-40% of the entire dictionary, especially given that such a disproportionate number of forms begin with alif (almost 1,000!).

Continue reading